[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ basename /library/training/Intro_to_Linux

Intro_to_Linux

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ dirname /library/training/Intro_to_Linux

/library/training

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ Filesystem

In this section you will learn how to explore the Linux file system, and how to create, move, delete and edit files and directories.

Introducing the Linux file system

Key Points

- In Linux, like other operating systems, the file system is structured as a tree

- The top-level directory is known as the root directory, and is referred to on the command line as

/

- The top-level directory is known as the root directory, and is referred to on the command line as

- The file system contains regular files, directories, and symbolic links to other files

- Each file has a unique path in the file system, along with other attributes such as its size, when it was last modified, and the permissions associated with it

- Each user’s files are generally stored in a directory called the user’s home directory, also referred to as

~- Home directories are normally found in

/home

- Home directories are normally found in

- bash keeps track of the current working directory that the shell is in

- When a user logs in to a Linux system, it starts in the user’s own home directory by default

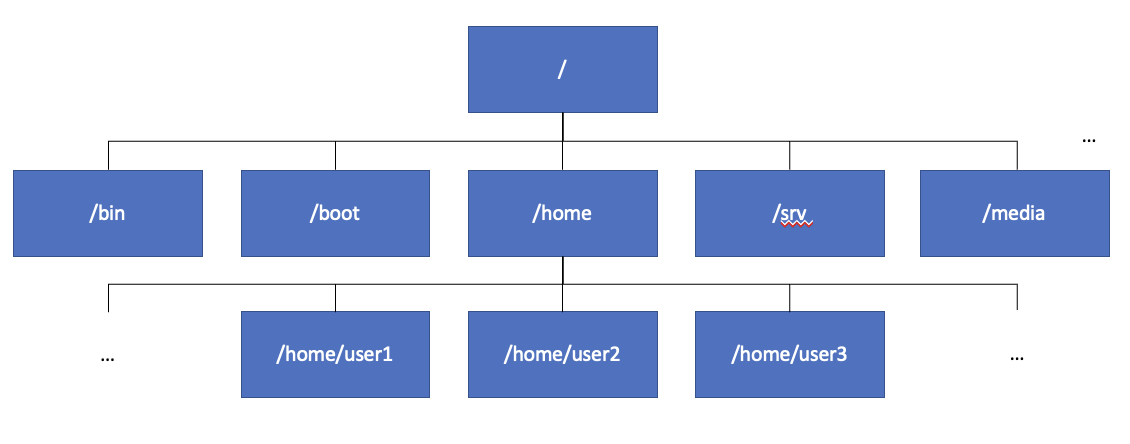

The Linux file system

The Linux file system, where all files in a Linux system are stored, is structured as a tree with a single root directory, known as /, as shown in the above image. The root directory has a number of sub-directories. The most important for us is /home as this is where users’ home directories are stored*. Each user’s files are generally stored in their home directory, and by default users are not permitted to create files outside their own home directory. You can find out the path to your home directory by running the command echo $HOME.

*On the bifx servers, home directories are located at /datastore/home as home accounts are securely stored on the university DataStore cloud storage. However, /home will still work as it is set up as a shortcut.

File paths in Linux

File paths in Linux can be either absolute paths, or relative paths.

Absolute paths

Each file in the Linux file system tree is uniquely identified by its absolute path. The absolute path comprises a list of the parent directories of the file, starting from the root directory, separated by the / character, followed by the name of the file. The name of a file, and the path to its parent directory, can be extracted from its path using the basename and dirname commands:

In Linux, file names can contain almost any character other than /. However, many characters, including spaces and special characters such as ’ and “, can make files difficult to work with, so, in general, it’s better to stick with letters, numbers, underscores, dashes, and dots when naming files. If you do have to work with a file that contains special characters, you can either put the file path in quotes or use backslashes to escape the special characters:

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ basename /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/file name with spaces

basename: extra operand ‘with’

Try 'basename --help' for more information.

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ basename '/library/training/Intro_to_Linux/file name with spaces'

file name with spaces

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ basename /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/file\ name\ with\ spaces

file name with spaces

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$Note: Tab completion works with file and directory names as well as command names. Try to use the command above by typing basename /libr and using tab completion to find the file file name with spaces.

The pwd command shows the absolute path of the current working directory:

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ pwd

/datastore/home/[USERNAME]

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$Relative paths

While absolute paths provide an unambiguous way of referring to files, they can be cumbersome. For this reason, Linux makes it possible to define paths relative to the current working directory or the user’s home directory:

~refers to the user’s home directory.refers to the current working directory..refers to the parent directory of the current working directory../..refers to the parent directory of the parent directory of the current working directory,../../..refers to the parent directory of that directory, and so on

If you just use the name of a file, Linux assumes that you are referring to a file in the current working directory.

The realpath command can be used to show the absolute path corresponding to a relative path:

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ realpath ~

/datastore/home/[USERNAME]

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ realpath .

/datastore/home/[USERNAME]

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ realpath ..

/datastore/home

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ Glob patterns

Linux also makes it possible to include wildcards in file paths, making it possible to refer to a group of file paths at once. Paths that include wildcards are called glob patterns. Useful wildcards include:

*which matches any sequence of characters?which matches any single character[]which matches a single character within the square brackets- for example, [aA] would match ‘a’ or ‘A’

- ranges of numbers are allowed, so [1-5] matches 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5

When bash sees a glob pattern, it expands it into a list of file paths that match the pattern (separated by spaces).

First, let’s look at the structure of files and folders in the directory /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes by using the tree command:

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ tree /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes

/library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes

├── human

│ └── hg38

│ └── genome.fa

└── mouse

├── GRCm38

├── mm10

│ ├── cpg_islands.bed

│ ├── genes.bed

│ ├── genome.fa

│ └── repeats.bed

├── mm9

│ └── genome.fa

└── UCSC

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$This contains two sub-folders, human and mouse. Within each, there are further sub-folders for different genome versions. Some of these contain files with genome sequence and annotation data.

A convenient way to experiment with glob patterns (and to make sure they match the files you want them to) is to use the echo command, which prints its arguments to the command line. Try the following commands:

echo /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/*

echo /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/mouse/mm?

echo /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/mouse/mm*Challenge:

Create a glob pattern that matches /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/mouse/GRCm38 and /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/mouse/UCSC only.

Solution

Solution.

Solution:

One option would be find folders that start with G or U:

/library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/mouse/[GU]*

Another is to find folders that start with a capital letter by specifying the range A-Z:

/library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/mouse/[A-Z]*

Challenge:

Create a glob pattern that matches everything in /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/mouse except for /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/mouse/UCSC.

Solution

Solution.

Solution:

One option would be to match folders which contain a number anywhere in the name:

/library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/mouse/*[0-9]*

File types and attributes in Linux

The Linux file system contains three main types of file:

- Regular files, which contain data

- Directories, which contain other files or directories

- Symbolic links, which are aliases (or pointers) to files and folders

As well as its name and path, each file has a number of attributes associated with it, such as its size, when it was last modified, and the permissions associated with it. You can check the attributes associated with a file using the stat command:

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ stat /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/sequences.fa

File: ‘sequences.fa’

Size: 135 Blocks: 1 IO Block: 8192 regular file

Device: 27h/39d Inode: 1003792241 Links: 1

Access: (0644/-rw-r--r--) Uid: ( 500/user1) Gid: ( 50/group1)

Access: 2024-09-25 13:09:35.836470000 +0100

Modify: 2024-09-25 13:09:35.837141876 +0100

Change: 2024-09-25 13:10:28.019841000 +0100

Birth: -

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$The output of the stat command shows us:

- What type of file this is (a regular file)

- The size of the file (135 bytes)

- The identity and group of the owner of the file (user1 and group1)

- When the file was last accessed, modified, and changed

- The permissions on the file: Access: (0644/-rw-r–r–)

- The permission string is -rw-r–r–

- The first character of the permission string tells us whether it is a file or directory

- The rest of the string can be divided into three groups (rw-, r–, and r–), representing the permissions granted to the user that owns the file, the group associated with the file, and all users

- Groups are sets of users. Permissions can be set by group to give multiple users access to the same files.

- There are three types of permission. These are permission to read the file (

r), permission to write to the file (w), and permission to execute the file (x)

File permissions can be altered with the chmod command. You can read more about setting permissions here.

Challenge:

Who has permission to read the file ‘/library/training/Intro_to_Linux/sequences.fa’? Who is permitted to write to it? Is anyone permitted to execute it?

Solution

Solution.

Solution:

Everyone on the server can read the file. The user that owns the file can read and write to it. Nobody is permitted to execute this file.

Exploring the file system

Key Points

cdchanges the current working directory- Use

cd pathto move to a specified directory e.g.cd /library/training - Use

cd ..to move up a directory - Use

cdwithout an argument to return to your home directory

- Use

dirslists a history of directories you have moved between- The

lscommand lists the files in the current working directory - The

treecommand provides a readable summary of the files in the current directory and its subdirectories - The

findcommand recursively searches for files in the current file system

Try using the following commands to navigate within the file system, and view and find files:

## Move to the Intro_to_Linux directory

cd /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/

## List the contents of the directory

ls

## List the contents of the directory including hidden files and using human readable file sizes

ls -lah

## List all files ending .gz

ls -lah *.gz

## Find all files ending .bed in the mm10 genomess directory

find genomes/mouse/mm10/ -type f -name '*.bed'

## List the contents of the directory in a tree structure

tree

## Return to the home directory

cdNote: In this example we have used the command ls -lah. This is an example of a shorthand that you can use in the bash shell when specifying multiple flags. ls -lah is equivalent to ls -l -a -h.

-llist files and show attributes-ashow all files (including hidden files)-hshow file size in human readable format

Play around with the ls command to see how it behaves differently without these options.

Challenge:

List all of the paths to files named ‘genome.fa’ in the directory ‘/library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes’

Solution

Solution.

Solution:

Run find /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes -type f -name 'genome.fa'

Or, because we know where they are in the tree:

ls /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/*/*/genome.fa

Challenge:

Using the commands you’ve learned in this section, explore the /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/ directory on the server. Which organisms do we have genomes for? Which genome releases do we have for each of these organisms?

Solution

Solution.

Solution:

Run ls /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/* to list the contents of each directory in the genomes folder.

OR

Run find /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/genomes/ -maxdepth 2 -type d to list the sub-directories of the directories representing the organisms, which represent genome releases.

There is always more than one way to do things in Linux!

Creating and deleting files

Key Points

- Files can be created using:

touch, a command to create an empty file- A Unix text editor, like

emacsorvim - By redirecting the output of a program into a new file (we will do this later)

- Symbolic links can be created using

ln -s- A symbolic link is a shortcut to a file or directory that exists elsewhere

- On the bifx servers /home is a symbolic link to /datastore/home

- Check this by running

ls -lh /home

- Check this by running

- Directories can be created using

mkdir, and empty directories can be removed usingrmdir - The

rmcommand can be used to delete files, links, and directories along with their contents (using the-rflag to recursively delete the contents of a directory)- There is no recycle bin in Linux, so

rmshould be used with care! - The

-iflag can be used to prompt for confirmation before deleting files

- There is no recycle bin in Linux, so

The following example demonstrates how we can create and remove files, directories and links:

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ cd

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ mkdir course

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~$ cd course

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ mkdir -p dir1 dir2 dir3/dir4

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ tree

.

├── dir1

├── dir2

└── dir3

└── dir4

4 directories, 0 files

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ touch file1

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ tree

.

├── dir1

├── dir2

├── dir3

│ └── dir4

└── file1

4 directories, 1 file

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ cd dir1

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ ln -s ../file1

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ cd ..

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ tree

.

├── dir1

│ └── file1 -> ../file1

├── dir2

├── dir3

│ └── dir4

└── file1

4 directories, 2 files

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ rmdir *

rmdir: failed to remove 'dir1': Directory not empty

rmdir: failed to remove 'dir3': Directory not empty

rmdir: failed to remove 'file1': Not a directory

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ tree

.

├── dir1

│ └── file1 -> ../file1

├── dir3

│ └── dir4

└── file1

3 directories, 2 files

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ rm -ri *

rm: descend into directory 'dir1'? y

rm: remove symbolic link 'dir1/file1'? y

rm: remove directory 'dir1'? n

rm: descend into directory 'dir3'? y

rm: remove directory 'dir3/dir4'? y

rm: remove directory 'dir3'? y

rm: remove regular empty file 'file1'? n

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ tree

.

├── dir1

└── file1

1 directory, 1 file

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ rmdir dir1

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ rm -i file1

rm: remove regular empty file 'file1'? y

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$ tree

.

0 directories, 0 files

[USERNAME]@bifx-core1:~/course$The example demonstrates a number of commands:

touchto create an empty file- This can also be used to update the timestamp on an existing file

mkdirto create empty directories- Add -p when create nested directories that don’t exist yet e.g. dir3/dir4

ln -sto create a symbolic link to a file or directoryrmdirto delete empty directories, without deleting files or non-empty directoriesrmcommand- Add -r to remove directories (and their contents)

- Add -i to ask for confirmation before deleting

Copying and moving files and directories

Key Points

- Files and directories can be copied using

cp- To copy a directory along with its contents, use the

-rflag

- To copy a directory along with its contents, use the

- Archive files in tar format can be extracted using the

tarcommand - Directories can be synchronised using

rsync, which only copies updated files - Files and directories can be moved or renamed using

mv - Attributes of files and directories can be changed using

chmodchmodchanges the permissions on a file

Next, we will copy files and directories to our own workspace, extract archived files and update file permissions. Along the way we will see how various filesystem commands behave.

## Move into your course directory

cd ~/course

## Copy the files from the training directory to your course directory

cp /library/training/Intro_to_Linux/bioinformatics_on_the_command_line_files.tar.gz .

## Extract the files from the compressed tarball archive. A tarball is a single file which contains multiple folders and files.

tar -xzvf bioinformatics_on_the_command_line_files.tar.gz

## Take a look at the output

tree

## Make a copy of the bioinformatics_on_the_command_line_files directory

cp -r bioinformatics_on_the_command_line_files bioinformatics_on_the_command_line_files-copy

## Check the contents of both directories. They should be identical.

tree

## Move the README file in the copied directory and change its name

mv bioinformatics_on_the_command_line_files-copy/README README.txt

## Inspect the result

tree

## Remove the copied directory and its contents as well as the README.txt file. Because you use -i, you will be prompted before each file is removed.

rm -r -i bioinformatics_on_the_command_line_files-copy README.txt

## Check the contents of the directory again

treeThis example has demonstrated a number of commands:

cpto copy files and directories (with the-rflag set)- The

-aflag will preserve file attributes when they are copied

- The

mvto move files or directories- The second argument to

mvis the destination. This can be:- A file path to rename the file e.g.

mv file1.txt ../dir1/file2.txt - A directory path to move the file and keep the original name e.g.

mv file1.txt ../dir1/

- A file path to rename the file e.g.

- The second argument to

File permissions can be altered using the chmod command.

- It’s always a good idea to make raw data files read only as it makes it more difficult to remove or overwrite them accidentally

- the

a-wargument removeswrite access forall users - Check the

chmodman page for more details on how to change file permissions. For now it is fine to just know this is possible.

## Inspect the file permissions of the raw data file

ls -lah bioinformatics_on_the_command_line_files/raw_yeast_rnaseq_data.fastq

## Change the permissions on the file to make it read only

chmod a-w bioinformatics_on_the_command_line_files/raw_yeast_rnaseq_data.fastq

## Check the file permissions again

ls -lah bioinformatics_on_the_command_line_files/raw_yeast_rnaseq_data.fastq

## If you attempt to remove the file you will get a warning that the data is read only. Hit 'n' to cancel the command.

rm bioinformatics_on_the_command_line_files/raw_yeast_rnaseq_data.fastq